Bust of a Naiad

Attributed to John Gibson RA (1790 – 1866),

Carrara marble,

After 1827,

51 cm high

30 cm wide

26 cm deep

£22,000

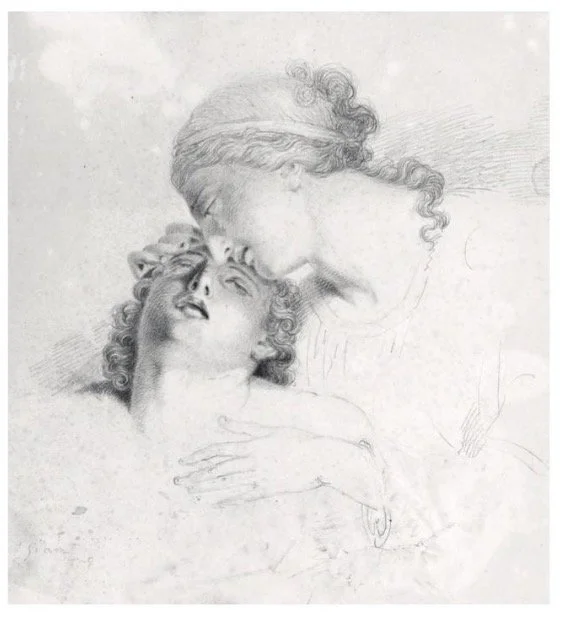

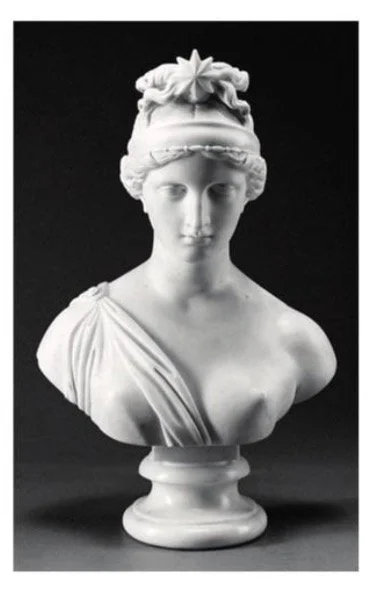

This finely executed bust of a Naiad is attributed to the neoclassical sculptor John Gibson (1790 – 1866). A Naiad was a type of mythological water nymph and is depicted here with her head bowed and cocked slightly to the side, displaying her strong neo-Hellenistic profile. In her hair, the nymph wears a headdress that is comprised of long and slender reed leaves, which not only identifies her iconographically as a water spirit, but draws a close comparison with those worn by the female figures in John Gibson’s Hylas Surprised by the Naiades (1827 - 1837) (fig.1). The downwards and off-centre orientation of our Naiad bust mirrors that of the taller figure on the left of the group, who rests her cheek on the head young Hylas (fig.2)

Her facial physiognomy follows the neo-Hellenistic archetype established by Gibson and can be closely compared with his Tinted Venus – one of the most important statues of the Victorian era (1851–56, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) (fig.3). While Gibson’s Tinted Venus is known best for its controversial polychrome ‘tinting’, the essential structure of the face—broad brow, finely drawn nose, wide (and slightly drooping) almond-shaped eyes - provided a template that Gibson returned to repeatedly in his depiction of mythological maidens. Critics of the time noted the consistency of his female types, with some seeing their idealised severity as an antidote to the sentimentality of much mid-Victorian sculpture (fig.4 – 6). The facial physiognomy is also very similar to a drawing by Gibson at the Royal Academy that depicts Hero weeping over the dead body of Leander (fig.7). The socle style of the present work also finds comparisons with Gibsons busts of Cupid and Aurora. This was of course somewhat standardised, but it is interesting to note the extent of their similarity with our bust.

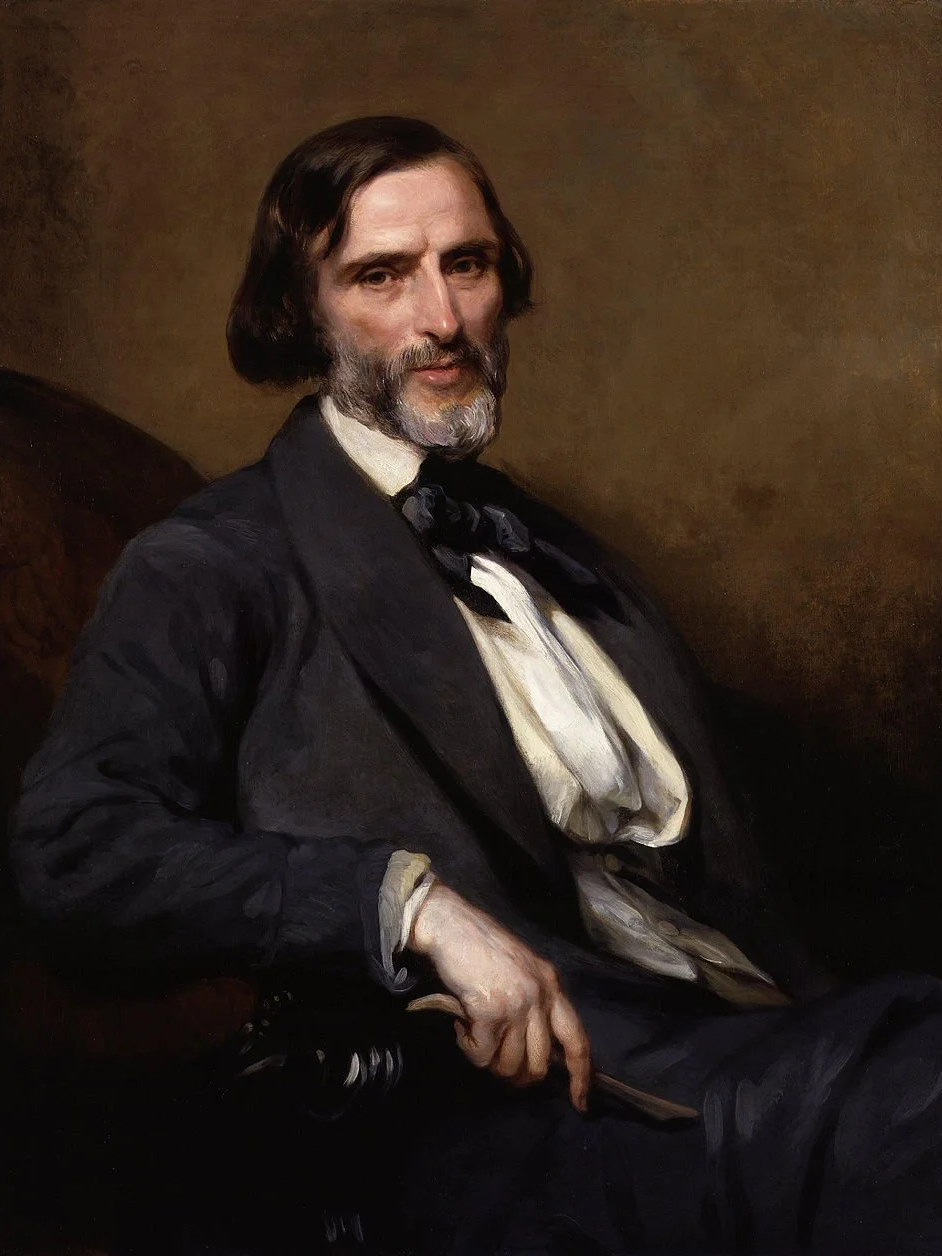

John Gibson RA is considered by many to be the greatest British sculptor of the nineteenth century working in the Neoclassical style. It is hard to overestimate the impact Rome had on the life and art of the artist. He first arrived in the city around 1817, when he was just twenty-six, and remained a resident there until his death. Not only did Rome’s ancient sculptural treasures and architectural fragments offer Gibson a lifetime of inspiration, but the Grand Tourists who poured into Rome in the first half of the nineteenth century provided him with many commercial opportunities. These rich or aristocratic travellers sought out mythological sculptures for their grand, palatial residences. However, since the papal decrees of Doria Pamphilj and Pacca of 1803 banned the export of ancient Greek and Roman works of art from Rome, there was a large demand for modern idealised sculpture in the Neoclassical style (Frasca-Rath 2016, p. 10).

During his early days in the city he had the great fortune to train under both Antonio Canova and Bertel Thorvaldsen (Roscoe and Hardy 2009, p. 522). He referred continuously to Canova as his “master”, particularly in his memoirs, which he dictated to Margarete Sandbach at the beginning of the 1850s; these were subsequently published by Lady Eastlake in 1870. Moreover, he claimed to be Canova’s last pupil in a letter to Antonio Gacini, Secretary of the Royal Academy in Milan in 1861, written to thank the Academy for accepting him as an Honorary Member: “The first instruction which I received in my art was from an Italian. It was Canova whose pupil I became in the year 1817 and studied under him for five years when he died. I was his last pupil” (Royal Academy Archive GI/1376). By 1821, Gibson had established his own studio in the via Fontanella, off the via Babuino. From here he aimed to produce sculpture of “the sublime and the purest beauty”, believing that the sculptor’s role was to select and combine the most beautiful parts of nature to create a harmonious whole, which would delight and elevate the viewer. By the mid nineteenth century he was one of the few remaining exponents of the so-called ‘pure’ and ‘neo Hellenistic’ style of sculpture, resolutely upholding the Neoclassical ideals established by Wincklemann, in a period when naturalism and modern subjects preoccupied the majority of artists in Europe (Turner, ed., 1996, p. 598).

Gibson was convinced of the importance of disseminating artistic ideas through the younger generations, an ideal no doubt impressed upon him by Canova, and established ‘the British Academy of Arts in Rome’. His students included William Theed (1804–1891), Benjamin Spence (1822–1866), Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908), Frederic Leighton (1830–1896) and Richard James Wyatt (1795 –1850), and this collection of British expatriate artists became affectionately known as ‘the Roman School of British Sculpture’. His impact on the young artists of the day is perfectly expressed by the bust of Gibson executed by William Theed in 1868 (Frasca-Rath 2016, p. 29).

Selected bibliography

M. Droth, John Gibson: A British Sculptor in Rome, New Haven & London, 2014

A. Yarrington, “The Greek Ideal and its Sculpture in Victorian Britain,” in Classical Victorians: Scholars, Scoundrels and Generals in Pursuit of Antiquity, Cambridge, 2007

A. Frasca-Rath, John Gibson: A British Sculptor in Rome, London, 2016

Lady E. Rigby Eastlake, Life of John Gibson, R. A., Sculptor, London, 1870, pp. 64–67

A. Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts. A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their Work from its Foundation in 1769 to 1904, London, 1905–06, vol. II, p. 230

T. Matthews, The Biography of John Gibson RA, Sculptor, Rome, London, 1911, pp. 66–67, 215

J. Turner (ed.), ‘Gibson’, The Grove Dictionary of Art, vol. 12, New York, 1996, p. 98

I. Roscoe et al., A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain, 1660–1851, New Haven and London 2009, pp. 24

Fig.1) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Hylas Surprised by the Naiades (1827 - 1837), Marble, Tate, UK (N01746)

Fig.1a) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Hylas Surprised by the Naiades (1827 - 1837), Marble, Tate, UK (N01746)

Fig.2) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Hylas Surprised by the Naiades (1827 - 1837), Marble, Tate, UK (N01746)

Fig.3) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Tinted Venus, 1851–56, marble and wax. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Fig. 4) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Tinted Venus, 1851–56, marble and wax. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Fig. 5) John Gibson (1790 - 1866), Venus, c. 1850s, plaster. Royal Academy of Art, London

Fig. 6) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Tinted Venus, first half of 19th century, marble. Sotheby’s London, 3-9 July 2020, lot 5

Fig. 7) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Hero weeping over the dead body of Leander, c.1822, pencil on paper. Royal Academy of Arts, London

Fig.8) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Bust of Cupid, white marble. Collection of Lord Garlis.

Fig.9) John Gibson (1790 – 1866), Bust of Aurora, 1843 – 1845, white marble. Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, USA

John Gibson RA (1790 – 1866)